(Photographed at Le Jardinier by Emilio Madrid for Broadway.com)

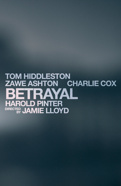

Betrayal Stars Tom Hiddleston, Zawe Ashton and Charlie Cox Relish Their Love Triangle

Harold Pinter’s 1978 drama Betrayal, is one of the Nobel Prize-winning playwright’s most popular works. It has been produced on Broadway four times and is currently on the boards in a starry, stripped-down transfer from London’s West End. The production, helmed by British director Jamie Lloyd, features Avengers star Tom Hiddleston, Daredevil’s Charlie Cox and Zawe Ashton as the show’s “throuple,” as Cox recently put it. Betrayal has always attracted big names; Raul Julia, Blythe Danner, Liev Scheiber, Juliette Binoche, John Slattery, Daniel Craig and Rachel Weisz have all appeared in the play on the Great White Way. Why is Pinter’s tale of infidelity and deception, told backward from the end of the affair to its first blush, such catnip for actors? Broadway.com sat down with the show’s current headliners at the posh restaurant Le Jardinier to find out.

“It is a modern masterpiece,” Hiddleston, who plays Robert, the betrayed husband in the piece, says. “It’s a play about relationships and intimacy and how three very complex people relate—three people, who at one time love each other and trust each other, betray each other. I think those are very human things that aren’t specific to any one era. People were like that in 1978, and people were like that in 1988, 1998, and here we are in 2019. And I think Pinter’s very specific analysis or presentation of these three complex relationships is very honest and very daring and very profound.”

Though there is one central affair in the play, there are many betrayals. The stars took a crack at counting them. “It’s a big catalogue, actually,” Ashton says about the nine or so they calculated. After noting the self-evident treachery of marriage and friendship, they looked into some of the less obvious betrayals in the play: “The betrayal of the children,” says Zawe Ashton, noting that each couple in the piece has two children. Then Hiddleston jokes about an unwritten character: “The betrayal of Judith by Harold Pinter!” Judith is the unseen wife of Cox’s Jerry.

On a more serious note, perhaps what makes the show so relatable is that no personal experience with infidelity is required from audiences in order to feel the show’s reverberations deeply. “There’s the portrayal of the younger self,” Ashton says, adding another betrayal to the list. “As you get older, you sometimes unwittingly betray your more youthful ideals. And because this is a play that’s told backwards, I think that’s something that people seem to be really getting a lot from is the play ends with these three people in the place of real hope. And that’s heartbreaking.” It’s especially poignant in a play that unspools backwards. “I think that’s what people are really responding to is that working back of the clock and thinking where did it all go wrong?” Ashton says. Cox agrees: “The past ends in the beginning,” he says. “And [we’re] exploring the idea that it’s only through the betrayal of oneself that you leave yourself open to be betrayed and to betray others.”

"You realize it’s not as simple as being a woman who’s torn between two men."

Hiddleston adds that by the time the show closes in December, the cast will have performed the piece for a full year. “As you do it iteratively, you discover more and more, and the one that I’ve got really interested in at the moment is the betrayal of poetry by prose,” he says. The two leading roles are in the publishing business, and the conversation of commerce versus art comes up. “Robert and Jerry are old friends,” Hiddleston says. “Their friendship was forged in a mutual admiration of poetry. Jerry was at Cambridge and Robert was at Oxford, and they were editors of poetry magazines. And now Robert’s a publisher and Jerry’s a literary agent, both very successful. But their success has been born on the back of the publication of prose novels, which aren’t in accordance with their youthful ideals. The authors that these two are publishing, or supporting—they’re not worthy of their respect.”

Another reason the plays resonates is the evenhandedness with which Pinter exposes the responsibility (or lack thereof) for the proceedings. It allows audiences to withhold judgment of characters lying and cheating, for example. “The more I understand the play, and the more I learn about Harold and his life, I think that is really fundamental,” Cox says about the lack of obvious blame in the drama. “I feel like that was part of a feeling that he had at the beginning of the process of writing it—that it would be wrong and it would demonstrate not a very deep understanding of human beings and life to be able to pin a responsibility very clearly on something in this situation. There are many responsibilities and you must hold everyone, even smaller parts played, accountable.”

The direction of this production has the three characters on stage together the whole time. Their physical presence evokes the triangulation of their predicament. “I think audiences get a lot from [the staging] because you can really feel the loneliness that each person feels underneath the facade of the scenes that they have together,” Ashton says. “You realize it’s not as simple as being a woman who’s torn between two men. You see a woman who’s really torn between two lives and two selves and someone who is as emotionally vulnerable as either of the men.”

"It’s only through the betrayal of oneself that you leave yourself open to be betrayed and to betray others."

This staging, which Hiddleston says puts the “characters in the same orbit” until they fragment off on their own trajectories, also offers audiences psychological insight. “I think it’s like a ghost for the characters in the scene,” Cox explains. “They’re haunted like Jerry and Emma are haunted by the ghost of Robert. It keeps [everyone] alive in the mind.” Ashton adds that having all the parties present also enhances the performances: “It really does inform what journey your character’s on, she says. “And for me, it informs the next scene, sometimes even when you want to leave that scene behind and enter into the scene anew. There is that residual energy that you carry into the next scene, and it’s just lovely. I actually don’t know what I would do if I had to go off to the dressing room and be on my own. I can’t imagine this play being done in any other way.”